''We all know the story. Virginal girl, pure and sweet, trapped in the body of a swan. She desires freedom but only true love can break the spell. Her wish is nearly granted in the form of a prince, but before he can declare his love her lustful twin, the black swan, tricks and seduces him. Devastated the white swan leaps off a cliff killing herself and, in death, finds freedom.''

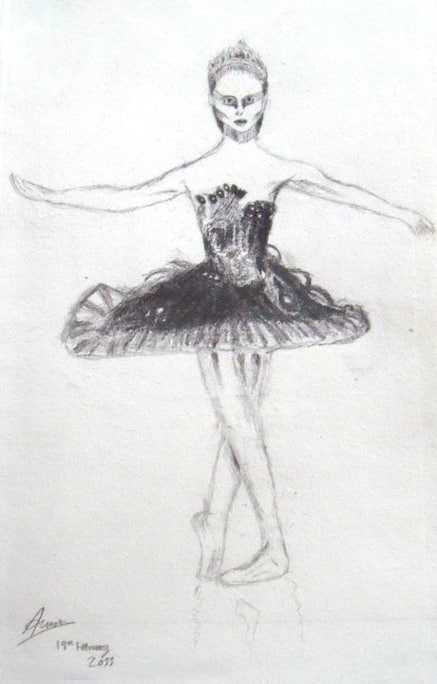

''We all know the story. Virginal girl, pure and sweet, trapped in the body of a swan. She desires freedom but only true love can break the spell. Her wish is nearly granted in the form of a prince, but before he can declare his love her lustful twin, the black swan, tricks and seduces him. Devastated the white swan leaps off a cliff killing herself and, in death, finds freedom.''A ballet dancer wins the lead in "Swan Lake" and is perfect for the role of the delicate White Swan - Princess Odette - but slowly loses her mind as she becomes more and more like Odile the Black Swan, daughter of an evil magician.

Natalie Portman: Nina Sayers

If you know Darren Aronofsky, if you understand his previous work and his way of doing things Black Swan will certainly be easy to work out. But even so, perfection is something hard to place in our reality, and Black Swan is exactly that. Hard to place,but nonetheless, an unrivalled masterpiece, nothing less. It was everything I expected and in some ways even more. The fact he has chosen Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake also has a special, personal significance due to it being one of my favourites. Darren is one of those like-minded individuals whom I can relate to in many ways.

Obviously Black Swan is eclipsed not just by the beautiful Soundtrack by Clint Mansell, and songs from Tchaikovsky, not only by the majestic cinematography, and costumes...The terrifying, transformation, acting from Natalie Portman. This is without a doubt her best performance to ever be captured upon the screen, and I can guarantee that she will win an Oscar. Affirmed and resolute, I felt this adamant even before seeing the film; That is how honed in I was regarding my instincts via clips alone.

Mila Kunis, Vincent Cassel,Barbara Hershey and a very dark Winona Ryder also give solid acting, gripping performances which are believable and poignant...But they sometimes feel as if they are just there for Portman to interact with. This is certainly not a negative factor, quite the opposite in fact.

Black Swan perhaps draws its strengths from the usage of close up camera angles, from shots that follow the character from behind, as seen in his previous works. Requiem for a Dream and The Wrestler are sometimes brought back to memory when we see a close up of a grapefruit, or we have a gripping finale which takes ones breath away. It is simply a magician at work, it is among the reasons why film-making is an art-form and means of expressing the very soul which resides in our very being.

Not since Pi or The Fountain has Darren harnessed that spiritual energy into something primordial, something dark, and Black Swan is the next piece to his master jigsaw puzzle. He is a master at work like a great renaissance painter, and as usual, the work speaks for itself, with elegance and purpose.

This is certainly, without a doubt, one of the best films to be released this year, and already should be considered among the best for this emerging new decade. It is surreal, erotic, seductive, destructive...Perfection. Ordered chaos, and Natalie Portman has given a spark and energy to the very fabric of performance and metamorphosis.

Black Swan is in essence, the perfect Swan Lake...And we will never see a performance like that again, the point is this; Perfection exists. But it only exists in that moment. The moment being the beautiful end.

''Because everything Beth does comes from within. From some dark impulse. I guess that's what makes her so thrilling to watch. So dangerous. Even perfect at times, but also so damn destructive.''

Login

Login

Home

Home 24 Lists

24 Lists 448 Reviews

448 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,